“Acorn Farm” by Lucy Gafford. 2017. Mobile, AL Public Art Collection. Photo courtesy Audrey Sanchez.

Getting Into Public Art

For many artists, landing a public art commission is a step on the career checklist. But breaking into a new part of the art world can be daunting, even for seasoned artists, especially if you’ve never created public art or applied to an RFQ before. Where to start? Good news: “Lots of folks are trying to bring in new artists,” says Barbara Neal, a public art consultant who’s worked in the field for more than 20 years. Arts organizations are creating programs for rural artists, young artists, and those using newer media, like sound, video, and ephemeral art, to broaden the scope. “Many public art programs are looking to bring new faces into the mix and really looking for diverse ideas. That’s a good thing,” explains Neal. If you’re debating taking the plunge…

1. Check yourself.

Public art isn’t just about making work in a studio. Road closure permits, insurance requirements, and materials acquisition are just a few examples of the non-art work that goes into making public art. “Not all artists are suited to public art,” says Brendan Picker, the Public Art Program Administrator at Denver Arts & Venues. “Public art can be really fulfilling, but it takes an artist willing to work with others—like the community, city agencies, etc.—to make it happen.” Make sure that branching out into this type of creation makes sense for you, both personally and professionally. For Toby Atticus Fraley, an artist who began creating for the public sphere in 2009, moving from galleries and festivals into public art was the right fit. “I like problem solving within restraints, like, ‘We have this green space, which has a 12-degree slope, where you can place an illuminated sculpture, but the power supply is 30 feet away.’ ”

Like Fraley did, ask yourself if public art seems like the type of challenge that suits your skills and creative or professional goals. Remember, too, that winning a commission often means focusing on a single project for a few months at a time. The likely result is time away from other work and other aspects of your art business.

2. Prepare and practice.

If you’ve never done anything remotely resembling public art, Picker suggests looking for opportunities to create art in public spaces, such as temporary installations or commissions on private property. Those types of experiences can help prepare you for working in public art. Thinking through the process and lifespan of an artwork is also beneficial, especially as certain materials are ill-suited to site conditions. Artworks placed outdoors are subject to all kinds of environmental challenges that a gallery piece would never face. Some concepts won’t make sense in the 24/7/365 world or in a specific community. Others, however, may be perfect.. “I had ideas that could only exist as public art pieces,” explains Fraley. Fraley’s Robot Repair began as a yearlong installation in an empty downtown Pittsburgh storefront. An updated version has existed at the Pittsburgh International Airport since 2015, where travelers peek through a window into the imagined world of aviation-themed robots. TIP: Gain more inspiration by visiting Public Art Archive™ where you can view collections and artworks from around the world, including those in your local community.

3. Read, read, read.

Administrators create detailed applications for a reason. Review the requirements, even reading them out loud if you need to, to make sure you meet the basic criteria before you apply. Double check that you can supply all of the requested items (such as a letter of intent, CV or resume, number of requested images, etc.). Carefully read the directions for applying, including making note of the dates and deadlines. “It’s super important is to read the RFQ about the site,” says Neal. “If the RFQ is describing an exterior, 3D piece, do not submit 2D examples (and vice versa). If we’re calling for paintings to create a collection for City Hall, please do not submit images of 3D work.” Speaking of images, also don’t give mockups until those are requested. RFQs generally ask for images of past work; renderings and proposals don’t come into play until semi-finalists have been selected who will be paid for that speculative work.4. Work smarter.

Another thing to keep in mind when contemplating applying is budget. It’s easier as a newer public artist to land a commission in lower ranges than to make the jump to big price tag commissions. By starting with smaller commissions, artists can build a portfolio and work up to higher budgets.

Many calls will include language explicitly asking emerging artists to apply; apply when you see one and use it as a learning experience. Neal explains, “There’s a lot more rejection than acceptance. Think about why you didn’t get it. Did you read the RFQ carefully? Was it a stretch to think the work you’ve done would be suitable for that place?”

Every new application is an opportunity to learn, in addition to being a job opportunity. And, as with any job, always tie your applications materials—your image selections, what’s included on your resume, your letter of intent—back to the call.

5. Showcase the best.

Picker advises: “Put your best images first. That way your best work is seen up front by any of the folks who review it during the jury process.” He suggests documenting all of your successful artworks before submitting your first application. Once you have an assortment of quality images to choose from, you can select the best, most appropriate works for any given call. “It’s going to pay off to have solid photos.” But use your images. Don’t try to pass off images of other people’s work as your own. “If you worked for another artist, it’s okay to include one image of something you assisted on but make it clear that it’s work you supported, not your work,” notes Picker. “We understand that artists help each other, but you want to be as clear and transparent as possible.”

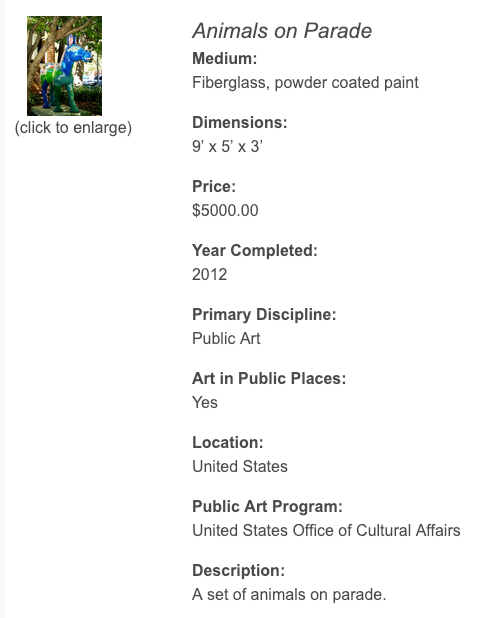

Picker also encourages CaFE™ users to complete the form fields associated with each image (such as site, title, description, price): “Those fields are actually pretty important. The panel might want to know ‘How much was that? What was the material?’ and those fields are key.”

6. Ask questions.

If you need help, ask for it! Public art administrators are interested in meeting new artists. If you’re not sure what something is, and a Google search generates more questions than answers, reach out to the call administrator. If calling or emailing is too nerve-wracking, attend a dedication when a new piece is installed in your community. “It might not hurt to go to a few of those and get into the network,” suggests Neal. “It lowers the temperature of that kind of entry. It’s more casual and informal and may not be as intimidating to meet people and ask questions.” But, remember, public art is about working with a community to make artwork for that community. “We want to help artists make that leap. We’re here to support artists. That’s one of the goals of the program,” explains Picker. In addition to the tips above, see our post “Better Your Chances at Landing a Public Art Commision” for even more advice from public art professionals on leveling up.Written by Leah M. Charney